Williams axed local pan press research

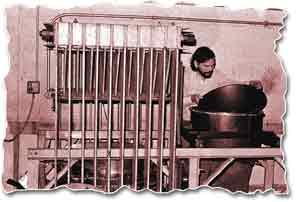

ClÉment Imbert, Project Engineer of the Steelband Research Project, looking at the bowl of a pan made by the hydroforming machine designed by Ron Dennis of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, UWI (1975).

By Terry Joseph

April 19, 2002

Petty politics prevented Trinidad and Tobago from registering the invention of a hydroform pan press more than 20 years before the American duo that eventually secured a patent for the process.

The locally developed hydroform press had already been commissioned and some 200 tenor pans pressed when then Prime Minister, Dr Eric Williams, shut off funding for the Caribbean Industrial Research Institute (Cariri) project.

And it was all due to peevish politics. Cariri chairman Eugenio Moore had fallen out of favour with Dr Williams, from whose office the project was being funded directly but by so loose an arrangement, it was easy for Dr Williams to simply shut off the money pipeline, scuttling all work in the process. Caught in the same crossfire was the development of George V Park, also under Moore’s chairmanship.

UWI senior lecturer Dr Clément Imbert, a metallurgist, headed the 1970’s Cariri project. Speaking yesterday to the Express, Dr Imbert said: "We got to the point of producing actual pans and their quality was approved by Anthony Williams and Bertie Marshall, the two tuners who worked with us on the project.

"Marshall and Williams consequently lost interest when work slowed due to lack of funds. I myself was absorbed into Cariri’s staff and therefore could not spend as much time on the project as when I headed it and did nothing else," Dr Imbert said.

The first batch of pans was pressed in Sweden by engineers at the automotive giant SAAB, who invented the original hydroform process, expressly for use in vehicle manufacture. Local engineers Richard Mc David and Imbert secured the pressing deal for Cariri. Molds were cast in Leicester, England, on the advice of SAAB and at minimal cost to the project.

"But by the time the molds were made and the pressed pans arrived here," Dr Imbert continued, "I had become disenchanted by the money squeeze and left Cariri. Apparently when the pans came in 1980, no one was actively in charge of the project and every last instrument simply disappeared from the premises. Luckily, the pressing plant had held back one for me.

"The hydroform press resulted from what, as far as I know, was the first scientific study of the characteristics of pan. It was initiated by Ron Dennis, an Englishman, one of my lecturers at UWI," Dr Imbert said. "I worked for him as a summer student in 1972.

"We analysed the behaviour of pan notes in the lab and I continued the work as my final year project for a BSc degree in 1973, showing pans could be pressed by the hydroform method.

"Our equipment was inadequate. We could only do mini-pans as we had a small die, which had been made in the year previous but had some bugs. I got rid of them and that being successful, Dennis got Cariri involved in the following year.

"Dennis designed the larger press and it was built in UWI’s Faculty of Engineering in 1974. When I left university, I went to Cariri, where Rodney Harnarine was in charge of the project. He left to take up a position with the Bureau of Standards and Mc David succeeded him.

"I was put in charge of completion and commissioning of the press. By 1975 the machine was built and tested. Caroni Ltd was very helpful, as we did not have large enough lathes to work with and they volunteered their machine shop for the duration of the project.

"From 1975 to ’76 we pressed a number of pans on that machine. Marshall and Williams, our two tuners would take the pans away, tune them and then report on whatever difficulties they encountered. They were both very interested.

Marshall had done his own experiments with electronics and before joining the team, Williams had actually worked with sheet metal as a substitute for oil drums.

"Our main problem with the hydroforming process was distribution of material. Williams and Marshall said the pans tuned well, but we were still not getting the right reduction in thickness on pans from the press. We continued working at improving efficiencies and proudly put out a first full set of pans, which were used at the Panorama competition of 1976 and came out on the road at Carnival, all through the kind courtesy and support of Ray Holman.

"You will understand that Cariri could not get involved in the political squabble, so the project effectively crashed in mid-1977. We formally recognised it as a lost cause. I had put off a scholarship and my wedding to work with the project and now it had been scuttled. Having been project chief, I wrote a full report (which is still there) and that, I thought, was the end.

"We never patented the process because we didn’t quite complete it. I went to England in 1978 to do my Masters Degree in Metallurgy and on my return, Cariri called me back to handle a situation completely unrelated to the pan project. In fact, it was for BWIA, an aircraft welding certificate course.

It was while I was there that Mc David called me and asked me to meet him in Belgium to do quite another job.

"We were sourcing equipment for Jack Ramoutarsingh for use in his steel plant. I met Mc David in Brussels at the ACP (Association of African, Caribbean and Pacific States) headquarters to proceed with that, but one of his missions was to go to SAAB in Sweden to discuss possible continuation of work on our hydroform press.

"Bertie Fraser was president of Pan Trinbago at the time and we told him of the price of the press, which was about TT$800,0000. The money was not available. We asked engineers at SAAB if we could use their machine to press out 100 pans in different materials (we were also using brass) so we could try out our concepts under the best conditions.

They agreed and perhaps because they want us to buy their machines, they actually pressed 200 pans.

"More than ten years later, when Pan Trinbago got promised its first set of money, I was asked to do a feasibility study and ammortisation plan for the press, because thy wanted to build a pan factory. However, the money is only now becoming available. It is reasonable to assume the press might now cost millions," Dr. Imbert said.

But even so massive a career disappointment has not daunted Dr. Imbert. Since late 1999, he has been visiting a number of pan researchers around the world, gathering and updating information.

"In the 90s I started to hear about this one and that one doing pan research but I noted that none among them was a metallurgist," Dr. Imbert said. "At my own expense, I started doing the rounds. Among the experts I visited was Ellie Mannette, Felix Rossing at NIU (Northern Illinois University) and a research went. I have, in fact, started back to work," he said.

Looking to the future of pan manufacture, Dr. Imbert felt research was too close to completion for mistakes to be made now. "There is a feeling in the pan fraternity that the only way or the best way to get best sound is to deform the drum by hand." This may or may not be true.

"But when a tuner takes ten years to fully understand how to work with the metal he is accustomed to, it may not be that easy to convince him to go through another learning process again. Today, the bottom line of nay pan whether pressed or sunk by hand is how well it sounds upon completion."

"There is not easy a machine can come close to tuning a pan as we know it." Dr. Imbert said. "It could shape the notes and get close to their fundamentals. The manufacturer could do rough tuning before firing and then fine tune after but our tuners here are likely to come up with better sounding instruments although the reason for that is even more interesting."

"A local tuner operates on a version of hit and miss. Not their skills, but if they get a good drum, a better pan will result. However, when a turner holds on to a not-so-good pan, he seldom throws it away, because his losses will be far too great. He would spend weeks trying to prove he could make it work before giving up or completing the job and selling the instrument for less. "

"If he were getting consistently good row material, he wouldn’t do that. The technical is therefore affected by economic considerations. It is one of the problems that a uniformly produced pan would solve, but there are difficulties on that side of the coin too. "

"The Americans plan to work with stainless steel, instead of the mild-steel we get from oil drums. The only deficiency of stainless steel is that it is a harder material to work.

"On the supply side, stainless steel will last much longer. It is more expensive. But if you consider how much longer it will last and be better protected that chromed pans for all its life. It then all boils down to business. The better pan but at what, price," Dr Imbert said."

Previous Page / Terry's Homepage